Time evolution of integrals

In many applications, one needs to calculate the rate of change of a volume or surface integral whose domain of integration, as well as the integrand, are functions of a particular parameter. In physical applications, that parameter is frequently time t.

Contents |

Introduction

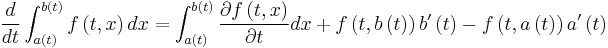

The rate of change of one dimensional integrals with sufficiently smooth integrands, is governed by this extension of the fundamental theorem of calculus:

The calculus of moving surfaces[1] provides analogous formulas for volume integrals over Euclidean domains, and surface integrals over differential geometry of surfaces, curved surfaces, including integrals over curved surfaces with moving contour boundaries.

Volume integrals

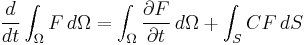

Let t be a time-like parameter and consider a time-dependent domain Ω with a smooth surface boundary S. Let F be a time-dependent invariant field defined in the interior of Ω. Then the rate of change of the integral

is governed by the following law[1]:

where C is the velocity of the interface. The velocity of the interface C is the fundamental concept in the calculus of moving surfaces. In the above equation, C must be expressed with respect to the exterior normal. This law can be considered as the generalization of the fundamental theorem of calculus.

Surface integrals

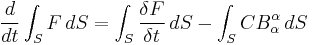

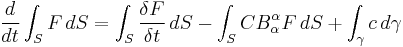

A related law governs the rate of change of the surface integral

The law reads

where the  -derivative is the fundamental operator in the calculus of moving surfaces, originally proposed by Jacques Hadamard.

-derivative is the fundamental operator in the calculus of moving surfaces, originally proposed by Jacques Hadamard.  is the trace of the mean curvature tensor. In this law, C need not be expression with respect to the exterior normal, as long as the choice of the normal is consistent for C and

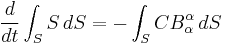

is the trace of the mean curvature tensor. In this law, C need not be expression with respect to the exterior normal, as long as the choice of the normal is consistent for C and  . The first term in the above equation captures the rate of change in F while the second corrects for expanding or shrinking area. The fact that mean curvature represents the rate of change in area follows from applying the above equation to

. The first term in the above equation captures the rate of change in F while the second corrects for expanding or shrinking area. The fact that mean curvature represents the rate of change in area follows from applying the above equation to  since

since  is area:

is area:

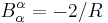

The above equation shows that mean curvature  can be appropriately called the shape gradient of area. An evolution governed by

can be appropriately called the shape gradient of area. An evolution governed by

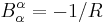

is the popular mean curvature flow and represents steepest descent with respect to area. Note that for a sphere of radius R,  , and for a circle of radius R,

, and for a circle of radius R,  with respect to the exterior normal.

with respect to the exterior normal.

Surface integrals with moving contour boundaries

Suppose that S is a moving surface with a moving contour γ. Suppose that the velocity of the contour γ with respect to S is c. Then the rate of change of the time dependent integral:

is

The last term captures the change in area due to annexation, as the figure on the right illustrates.